If you would like to check out IV Infusion Compatibility Auto-Compiler, please click here.

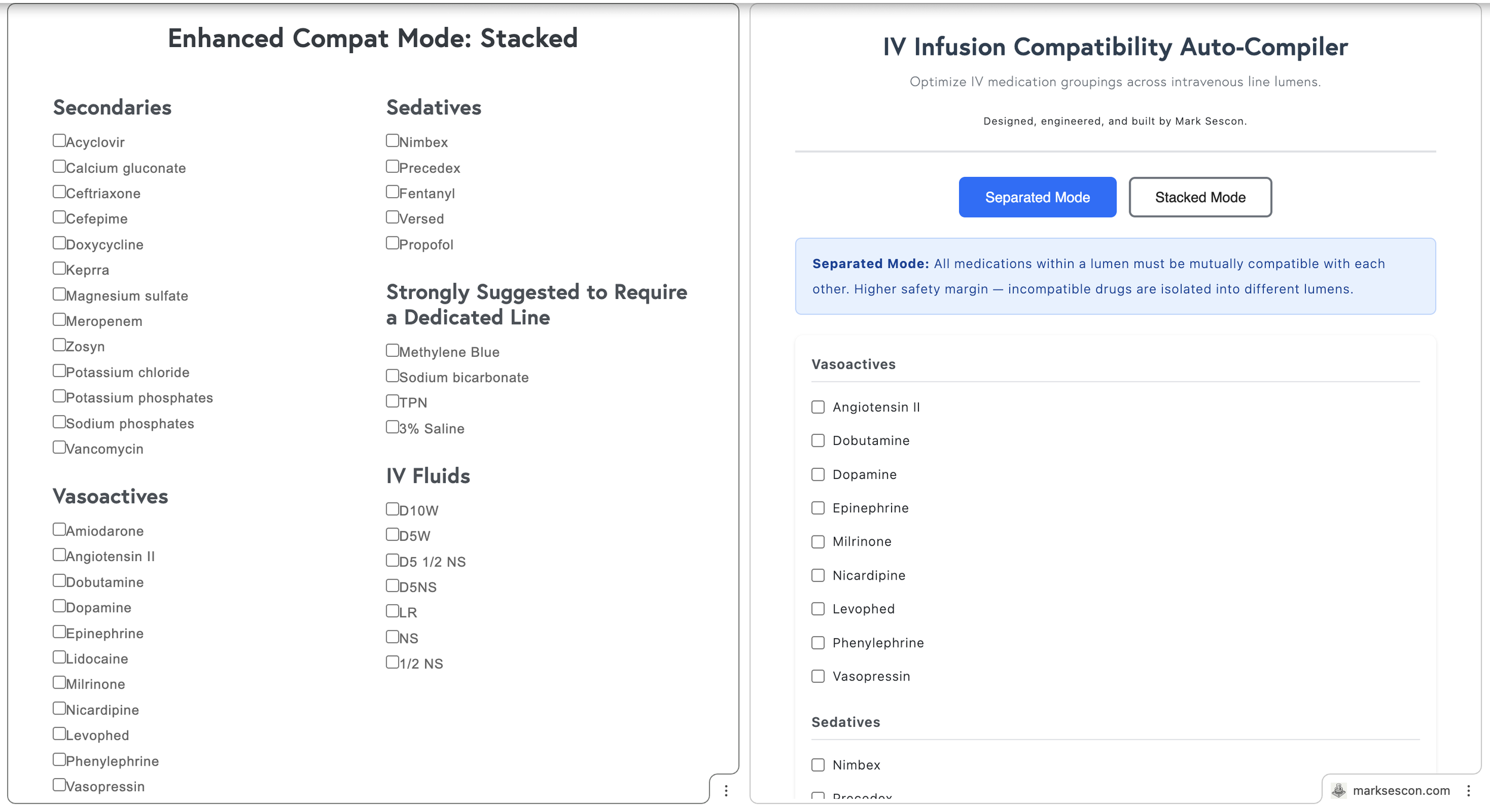

A year ago I built a web app called Enhanced Compat Mode that checked IV infusion compatibilities and came up with the best combinations of 2 to 3 main infusions across as few IV lines as possible and with considerations made to secondary infusions. Nurses could use it to figure out how to organize compatible IV infusions on the fly. Furthermore, I wanted to rename it to something more sensical: IV Infusion Compatibility Auto-Compiler.

The app differentiated between two modes:

Stacked Mode maximized lumen efficiency by allowing incompatible secondary medications to share a line, provided they were each compatible with the primary infusion and scheduled to run sequentially rather than simultaneously. For example, a patient receiving vasopressin, potassium phosphate, and magnesium sulfate can have all three infusions assigned to the same lumen in Stacked Mode. Although potassium phosphate and magnesium sulfate are incompatible with each other, they are both compatible with vasopressin, and since they will not run at the same time, they can share the lumen.

Separated Mode prioritized safety by requiring all medications within a lumen to be mutually compatible, isolating incompatible drugs into different lumens entirely. For example, a patient receiving norepinephrine, vancomycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam (Zosyn) can only have compatible medications grouped together. If vancomycin and Zosyn are incompatible, Separated Mode will automatically assign them to separate lumens to prevent any risk of adverse interactions. This approach is particularly useful for patients requiring multiple antibiotics or electrolytes administered simultaneously.

In the original iteration, Stacked mode worked well, however, Separated mode was not reliable. The problem was a greedy algorithm.

For example, Vasopressin, Magnesium Sulfate, and Potassium Phosphate. Vasopressin is compatible with either of the other two, but Magnesium Sulfate and Potassium Phosphate are incompatible with each other. The optimal output is two lumens with Vasopressin paired with one of them while the other on its own line. But the greedy algorithm consistently separated all three into isolated lines, because an early pairing decision blocked the better arrangement.

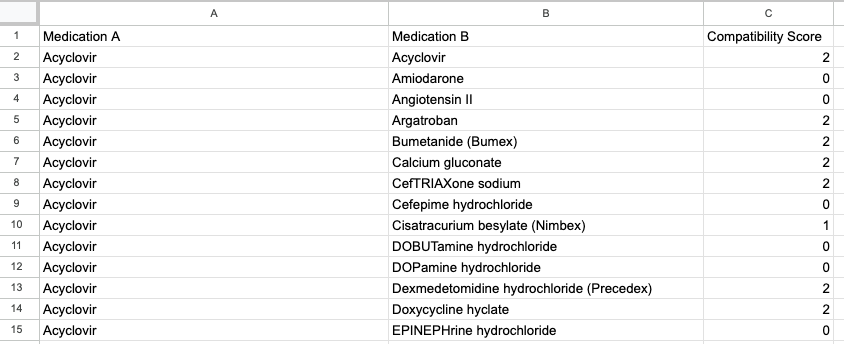

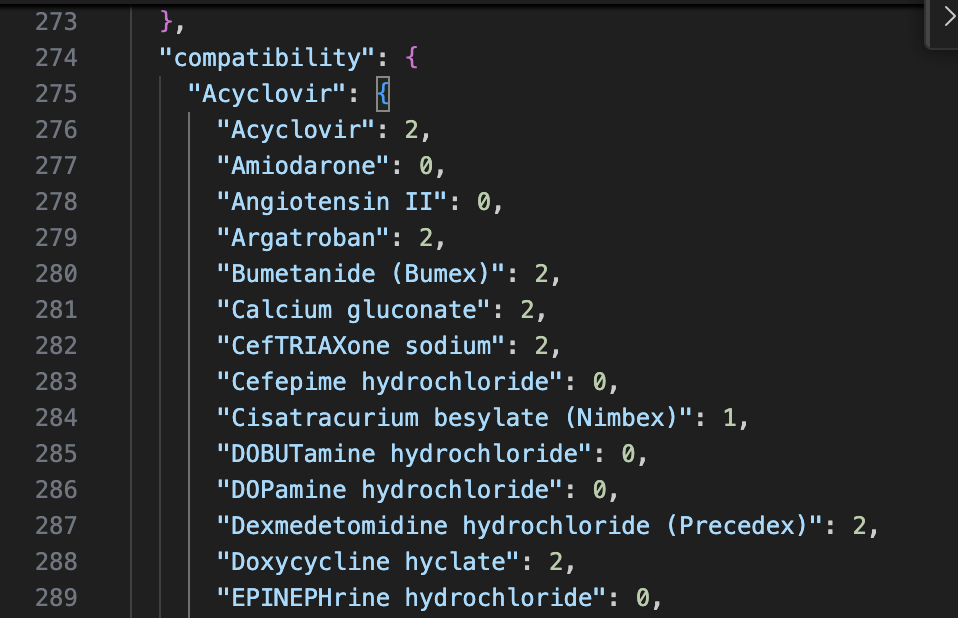

Compatibility data was derived from resources like LexiComp, Pepid, and Stabilis. Then the compatibilities were manually recorded in a Google Sheets file with values of 0, 1, or 2. Values of 0 meant incompatible or unknown; 1 meant variable; and 2 meant compatible.Utilizing an AppsScript, I was able to convert the data to JSON format. The resultant JSON file was separate from the code and gave the app scalability.

Google Sheets file.

JSON data.

New data could be added or old data updated without touching the code. The 1s were particularly tricky, since variable compatibility often comes down to concentration or diluent. I handled this with a Strict mode toggle, or a conservative (Risk-Averse) output that treated 1s as incompatible, and a liberal (Standard) output that included them but flagged them for further investigation. Categories in the metadata (vasoactives, sedatives, etc.) were mostly for the UI, making it intuitive for nurses to select medications with the exception of "dedicated" drugs, which were those that could only run alone.

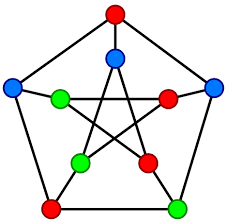

The greedy algorithm problem sat there for a while. After a year of growth in programming, I came back to it and finally saw what was really going on. This is a graph coloring problem.

Each medication is a node, edges connect incompatible drugs, and the goal is to assign the fewest "colors" (lumens) possible so that no two incompatible drugs share one. More precisely, it's a clique cover problem, or an issue with partitioning medications into the minimum number of groups where every drug in a group is mutually compatible.

I ditched the guess-and-check approach for a backtracking algorithm. Instead of grabbing the first arrangement that looks okay, the app now explores the entire decision tree. It starts by aiming for the absolute minimum number of lumens and tries to slot each medication in while cross-checking compatibility with everyone else already in that group. When it hits a dead end where no more drugs fit, it backtracks to the last successful step and tries a different path. To make this efficient, I added a heuristic that sorts medications by their number of incompatibilities first. By tackling the troublemakers early, the algorithm kills off impossible combinations immediately rather than wasting time on setups that were never going to work.

I highly recommend Learning Functional Data Structures and Algorithms by Atul S. Khot and Raju Kumar Mishra if you are interested in reading more about this approach.

I kept the strongly suggested maximum of three continuous infusions per line. While the backtracking algorithm is capable of organizing up to five medications per line, the Auto-Compiler is programmed to prioritize a "Rule of Three" safety threshold. This recommendation is rooted in clinical research showing that beyond three concurrent infusions, the risk of unpredictable pH shifts and micro-precipitation increases exponentially. Most binary compatibility data (1:1 testing) simply cannot account for the volatile chemistry of multi-drug cocktails (Keum et al., 2024).

In clinical chemistry, the transitive property does not exist. Just because Drug A is compatible with Drug B, and Drug B is compatible with Drug C, it does not guarantee that A, B, and C can safely coexist in the same line simultaneously. Most data is derived from binary 1:1 testing, which cannot account for the cocktail effect where the cumulative pH shifts of three or more medications may finally overwhelm the solution's buffering capacity and cause a drug to precipitate (Keum et al., 2024).

A critical mechanical constraint is the manifold dead-space volume. This is the stagnant fluid trapped within connectors, valves, and Y-sites that is not actively participating in the primary flow. In a complex manifold, this dead space becomes a reservoir for concentrated, high-alert medications. As you add more infusions to a single lumen, you increase this stagnant volume, which creates two major risks: accidental bolusing and delivery lag. If a carrier rate is adjusted or a line is flushed, that trapped volume of vasopressors is suddenly shunted into the patient, potentially causing harm to the patient (Lovich et al., 2013).

I updated the Stacked Mode algorithm to better reflect clinical reality by treating secondary infusions as sequential rather than concurrent. This change removes the max medications limit for secondaries, allowing an unlimited number to share a lumen provided they are compatible with the primary driver.

I updated the Stacked Mode algorithm to include a context-aware dynamic carrier fluid placeholder, which visually represents the primary saline infusion required for sequential piggyback administration. This feature allows the tool to better align with diverse hospital protocols by automatically injecting a "Normal Saline Primary for Piggybacks" label into any lumen grouping containing a secondary infusion. The UI remains clean by only displaying the toggle when Stacked Mode is active and secondaries are selected, and the system is now fully reactive, instantly updating the results table as the setting is adjusted.

Revisiting this project a year later has been a lesson in how software, much like clinical practice, is rarely a "finished" product. Identifying the flaws in my original logic and implementing a backtracking algorithm wasn't just a bug fix; it was about maturing the tool to match the actual complexity of my job. This evolution highlights that our programs should grow alongside our expertise. Building this was an iterative process that reflected my own growth as both a developer and a clinician.

References

Cassano-Piché, A., Fan, M., Sabovitch, S., Masino, C., Easty, A. C., Health Technology Safety Research Team, & Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (2012). Multiple intravenous infusions phase 1b: practice and training scan. Ontario health technology assessment series, 12(16), 1–132.

Lovich, M. A., Wakim, M. G., Wei, A., Parker, M. J., Maslov, M. Y., Pezone, M. J., Tsukada, H., & Peterfreund, R. A. (2013). Drug infusion system manifold dead-volume impacts the delivery response time to changes in infused medication doses in vitro and also in vivo in anesthetized swine. Anesthesia and analgesia, 117(6), 1313–1318. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a76f3b

Keum, N., Yoo, J., Hur, S., Shin, S. Y., Dykes, P. C., Kang, M. J., Lee, Y. S., & Cha, W. C. (2024). The potential for drug incompatibility and its drivers - A hospital wide retrospective descriptive study. International journal of medical informatics, 191, 105584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105584